RS2: The Orang-orang and the Hutan

Jump to

RS2 is one of the two studios for MA Environmental Architecture.

Architectures, anthrosols, and other medias of the inhabited forest

Addressing inter-sectional knowledges and spatial structures entangled within social and ecological tensions of a forest under fire, the studio will interrogate bio-resources – both extracted and extracted from – through the specific, elemental materials and processes that comprise the inhabited forest. In step with the global push for ‘clean’ energy and the prolific expansion of networked territories and network capacities, the increased availability of new technologies rapidly reconfigures traditional methods and communities of resource extraction. Increasing access to global production networks and global commodity chains significantly alters traditional structures of exploitation and unlocks new resource markets. These new markets are actively reorganising relationships – both seen and unseen – across vast territories of resource-rich terrain, particularly in the global south.

Working from the elemental to the geopolitical, students will design pathways of research and spatial interventions that highlight and engage with disputes between forest conservation, land rights policies, anthropogenic ecologies and economic evolutions in Borneo – an island shared by Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei.

RS2 proposes an alternative way of thinking and designing architecture and environments through platforms – physical and virtual – that act as forms of collective, political, and spatial practice. The studio encourages students to think simultaneously across multiple scales and medias, proposing architectural models and strategies for a wide array of collectives engaged in sites of environmental conflict. As in previous years, RS2’s main research question is: What kind of architecture could emerge when we think about and design with environments that shift paradigms of empowerment towards justice?

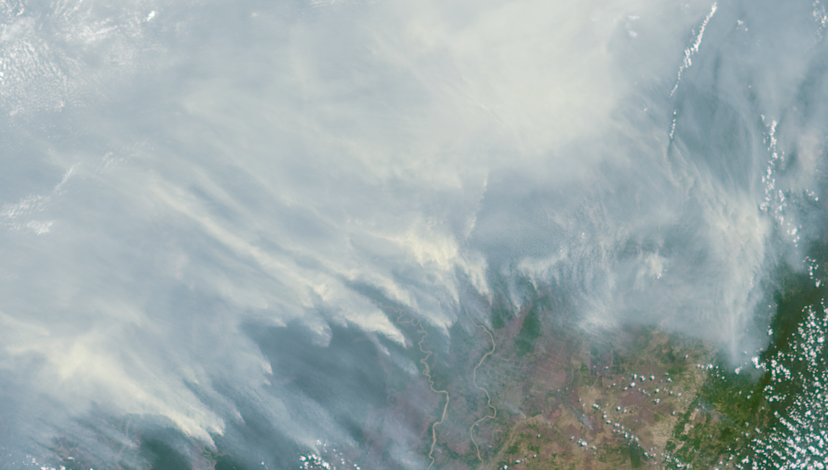

Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) Burning, September 2015: NASA Satellite Imagery.

Context

Driven by a growing demand for – and investments in – palm oil and other bio-industrial cash crops for food and energy and coupled with carbon-storage trading initiatives such as the UN-backed Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) scheme, the exploitation of resource-rich regions has intensified rapidly in recent decades. Attracted by a remarkable potential for fast and vast profits, the actors behind these processes are as diverse as the drivers. Rising out of clashing interests, perspectives, and power relationships, various types of conflict – often accompanied by a weakening of state control – over rights to land and resources result in multi-scalar forest degradation. Misunderstood, complex forest ecologies and insufficient data contribute to poorly enforced regulatory policies. In this context, local indigenous tribes have turned to new technologies to operationalise opportunity – and resistance.

Burnt soil, Commercial Palm Oil Plantation, Central Kalimantan, January 2019: Christina Leigh Geros

Focus

Tropical peatlands are found across Southeast Asia, Africa, Central and South America, and the Pacific – each with its own history of human occupation. Peatlands – or swamps – are carbon-rich, biologically diverse ecosystems and material commodity. Peat forms through a process of long-soaked decaying vegetal matter in tannin-rich waters; the resultant organic material, which stores up to twenty times more carbon than non-peat mineral soils, gradually accumulates, layer upon layer, over hundreds or even thousands of years. As a material, peat has been utilised, valued, and lived with variously around the globe. Too wet to burn, cultivation practices of peatlands have developed around a form of swidden – or slash and char – farming. Deep pockets of peat produce long, smouldering fires; restructuring soil nutrients and water-holding capacities into more stable organic matter capable of a full index of fertility. Over thousands of years these assemblages of human forest relations, or anthrosols, have transformed pockets of previously nutrient-poor soils into highly productive lands.

In these material contexts, the value of the traded commodity must be examined through the specific soil, air, water, and human dynamics that produce them. Industrialised in space and time, modern capital demands have taken their cues from traditional practices – engineering vast territories into cash crop monocultures, particularly oil palm and acacia, effectively transforming ‘wastelands’ into profit margins. As significant carbon sinks, the burning of each hectare of peatland emits an average of 55 tonnes of carbon dioxide and the Industrial scale slash and char farming has helped induce a frenzy of activity in the ‘carbon banking’ industry. Anthrosols are the not-yet recognised markers of the ongoing economic and elemental reconfiguration of the Earth.

Commercial Palm Oil Plantation, Central Kalimantan, January 2019: Christina Leigh Geros

Locus

Worldwide, there are approximately 450 million hectares of peatland, of which about 12 per cent are in the tropics. While Indonesia alone possesses nearly 50 per cent of total tropical peatland area, an estimated 20.9 million hectares, the development of productive anthrosols – past, present, and future – requires a specific set of geographic and anthropogenic circumstances. The third largest island in the world, Borneo is home to approximately 5.76 million hectares of peatland with an estimated occupation by ‘modern humans in the Bornean rainforest for over 50,000 years’. Over two-hundred ethnic subgroups of Dayak, or native peoples of Borneo, occupy the island’s riverine and mountainous terrain, developing a varied set of relationships and customs in forest knowledge, use, and cohabitation.

However, rapid and extensive forest conversion for bio-industrial crop production and large scale mining operations has reconfigured ecologies and redistributed populations. Despite a 2009 government moratorium on deforestation, it is estimated that 400,000 hectares of land per year are being lost across the archipelago – 160,000 hectares annually in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) alone. In addition, there are 2.1 million hectares of disputed land claims, with 400,000 in West Kalimantan Province. To address these claims, the Indonesian government has implemented two significant programmes in effect since 2013. Meanwhile, the national courts have ratified constitutional amendments giving indigenous peoples the right to assert land ownership within state-owned forests. Due to these programmes, official government reports show the decrease of figures under dispute; however, conditions on the ground evidence otherwise, as these programmes tend to complicate forest management and conservation law.

Dayak communities have traditionally practised various forms of artisanal mining, forest agriculture, and selective logging, with the spatial distribution of Dayak villages and their activities woven into the web of the industrial-scale plantations and their infrastructures. In Kalimantan, self-mobilised local activists have been using drone imaging and online networks to document land concession violations. Against this growing appetite of industry and global demand, local forest inhabitants continue to raise new land claim disputes-but without a clear path towards action.

The Indonesian archipelago is one of the most resource-rich territories in the world with a long history of multi-scalar extraction practices. After the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesia embarked on a process of democratisation and decentralisation ushering in two concurrent resource booms: in the mining sector, including oil, gas, coal and minerals; and in the cultivation sector, primarily through the processing and export of palm oil. With poverty reduction as a primary objective for the nation, the booming extractives-led economy has been of interest to both local and global markets. Estimates hold total losses of intact forests in Indonesia to as much as 72 per cent, with 74 million hectares of rainforest being burned, logged, or degraded in the last half-century alone. Storing approximately 35 billion tonnes of carbon, Indonesia’s peatland forests are considered the world’s largest carbon sinks – when burned, they release thousands of tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

In 2015, between June and October, 2.7 million hectares of land were burned, inadequately controlled, for cheap access and industrial agriculture. With significant health, environmental, and economic costs not only nationally, but across Southeast Asia, Indonesia’s forest management policies and regulations have come under significant international scrutiny. The 2015 Paris Agreement adopted at COP21 provides strong support for the REDD+ Programme, which aims to cut emissions by financially incentivising – through international funding schemes – reductions in deforestation and forest degradation while promoting conservation and sustainable management practices to enhance forest carbon stocks in developing countries. However, like the extractive-practices they aim to reduce, such programmes also disrupt the social and ecological systems within which these ecologies are embedded. Western ideals of conservation and environmentalism often exclude human occupation; however, the Indonesian forest has always been an inhabited one and the fight for local voices within national – or international – management schemes and financialisation plans is an ecological battle.

Commercial Palm Oil Plantation, Central Kalimantan, January 2019: Kaiwen Yu

The watery carbon sinks of Central Kalimantan, from the air, July 2016: Christina Leigh Geros.

Scope

The people and the forests – the Orang-orang and the Hutan – of Borneo present a unique case within a global context of forest commodification, shifting fuel economies, and geo climatic political action. Further complicating human-forest relations in Borneo, mobile communication and imaging technologies amplify means of forest capitalisation and methods of resistance. These communications give voice to variations between lived, local experience and regional – at times, national and international – projections. Exemplifying the multi-scalar and interconnected processes of feeding and fuelling the global population, the project of Environmental Architecture reckons with both real costs and potential opportunities created by planetary urbanisation.

Intense geopolitical pressures and shifting capital interests – from bio-industrial cash crops to capital-driven reforestation programmes – impact on-the-ground realities for communities within forest ecologies. Read through the centripetal accumulations of capital, operational extractive landscapes tend to be characterised by particularly uneven development – specifically in terms of gender and ethnicity.

Combining spatial and ethnographic design methodologies, students will engage with local communities, activists, ecologists, and government officials through participatory methods and protocols of reciprocity that will enable long-term co-design and intervention. Refuting the common notion of export product as commodity through an examination of the elemental

materials of the environments that produce them, the MA Environmental Architecture programme endeavours to design operational research methods capable of empowering and shifting momentums of the social, spatial, and ecological processes and relations that create these fertile materials as a means to decolonise ideas of conservation and valuation of the inhabited forest.

Indonesian Forests on Fire, September 2015: Source unknown.

Research partners

The studio engages with both government and non-government organisations in Indonesia, including the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, BNPB (Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana/National Disaster Management Agency), Kemitraan (Partnership for Governance Reform, Indonesia), BRG (Peatland Restoration Agency, Indonesia), and Pantau Gambut (an international organisation of 23 NGOs, including the World Research Institute, focusing on peatland knowledge and education practices). As primary collaborators, PetaBencana.id and WALHI (Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia) work closely with the studio to design spaces and interfaces for applied research and experimental response to environmental changes.

Additionally, the programme joins an international group of artists, researchers, and curators in a cross-cultural, curatorial, and artistic investigation into the environmental impacts of tropical peat forest destruction across Southeast Asia and Latin America. Through art and design practice, the ‘Haze Lab’ endeavours to question the many new social relations, bodily and ecological impacts found locally and globally. A series of workshops and exhibitions will be held across Southeast Asia, Latin America, Europe and the UK.

WALHI (Wahana Liangkungan Hidup Indonesia): A member of Friends of the Earth International and the largest independent, non-profit environmental organisation in Indonesia. Nationwide, their extensive network of researchers, community members, and environmental activists allow us to engage with residents of peatland ecologies – building our knowledge from indigenous epistemologies and engaging with participatory methods of knowledge building and dissemination.

PetaBencana.id: is a platform run by the Yayasan Peta Bencana as a free, transparent platform for emergency response and disaster management in megacities in South and Southeast Asia. Operationally based in Jakarta, the PetaBencana team offers a rich resource that helps to develop long-term relationships and communities of sharing that can offer pathways to action in both slow- and quick-onset environmental disaster events.

Student trip into the peat swamp with WALHI, Central Kalimantan, January 2019: Christina Leigh Geros.

How do we know what we know? From left to right: The Ciliwung River, Jakarta, Indonesia; Ancestral boundaries in peat forest in Central Kalimantan; Brain Machine Interface, Tokyo.

How do we know what we know? Lines of communication and rescue, flood in Kampung Pulo, Jakarta, Indonesia 2013.

Student interviews with local residents, Central Kalimantan, January 2019: Christina Leigh Geros.