Key details

Date

- 21 November 2023

Author

- RCA

Read time

- 28 minutes

Download the transcript

Join us as we discuss the fascinating and often overlooked world of public toilets, with guests Gail Ramster and Professor Jo-Anne Bichard.

Key details

Date

- 21 November 2023

Author

- RCA

Read time

- 28 minutes

Download the transcript

In the latest episode of the Royal College of Art Podcast, host Benji Jeffrey sits down with leads of the RCA's Public Toilet Research Unit, part of the RCA's Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design.

From the challenges of finding a decent public toilet to neglected design, and policy challenges hindering public loos' improvement, Gail and Jo-Anne share insights into their research and experiences.

Listen as they discuss the serious and humorous sides of their work, emphasising the need to break the taboo around loos and integrate them into broader discussions on urban design and accessibility.

Hear the episode on Spotify, Apple Podcast and YouTube.

Transcript

Benji Jeffrey 00:08

So we've all been there, you're out shopping maybe on your local high street or maybe somewhere new and unfamiliar. You're going happily about your afternoon picking up some groceries or trying to find a new pair of shoes when nature calls. And as the need to go increases, so does a sense of panic as you realise you have no idea where to find the nearest toilet.

Maybe you have a go to spot a familiar cafe or pub, or you spot somewhere more anonymous, like a fast food outlet where you can sneak in and be noticed or if you're lucky, maybe there's a library gallery or museum opened nearby. We've toilets for visitors. Perhaps you brave the public toilets, fearing wet floors, broken loose seats, and no toilet roll, or attempt to use them only to find them locked or out of order. Maybe you have no choice but to abandon your shopping trip and hope you can dash home in time. Providing somewhere to go to the toilet is not only a matter of public and social responsibility, but it is also one that makes business sense. Without toilets people are limited to the amount of time they can spend on high streets.

So what can design contribute? How can designers create toilets that are truly accessible but also sustainable and fantastic places to visit? This question is one of the many that are preoccupying Professor Jo-Anne Bichard and Gail Ramster here at the Royal College of Art, where they lead the Public Toilet Research Unit.

I'm your host Benji Jeffrey, and you're listening to the Royal College of Art Podcast. The Royal College of Art is the world's number one art and design University and home to the next generation of creatives. It represents the largest concentration of postgraduate artists and designers on the planet. And on this podcast we're taking a deep dive into what we do here. We're talking to staff students and the wider RCA community about how their work affects the world at large. And in today's episode, we're talking toilets.

Jo-Anne and Gail are part of the RCA Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, which is a research centre here at the College, which for over 30 years has been looking at ways that design can be used to solve challenges in areas such as healthcare, age and diversity. Jo-Anne is a professor of accessible design and a design anthropologist whose research involves collaboration across disciplines and actively including others in the design process. Gail is a senior research associate at the centre and her research addresses social challenges through participatory and co-design methods with citizens and communities. In our conversation, we discussed ways that designers of all disciplines from service design to experienced design can contribute to making toilets more accessible. They shared some of their experiences of how human centred design can help foster mutual understanding and make toilets better for everyone. And we look to the future of the toilet or ‘loo-topia’, as they like to call it. Jo-Anne and Gail, thank you for joining us today. How are you both doing? Let's get straight into the important stuff. Why are toilets so important to you both?

Jo-Anne 03:07

Well, from a professional from a design perspective. It's the one space in the built environment that practically everybody is going to use at some point during the day and night. And so it's really important that we get them as inclusive as possible. And that inclusion thinks about age and ability and gender, and social economic circumstances. We're trying to think about every issue that people might face as a barrier to accessing toilets. From a personal perspective, it's toilets. Everybody has a toilet story. And those stories are sometimes really funny. But always illuminating. Sometimes they're really sad. And again, equally illuminating.

Benji Jeffrey 04:02

What about you, Gail? How did you land on toilets.

Gail 04:04

So I have an engineering background and then came into design doing what was then called Industrial Design Engineering at the Royal College of Art. And I think with that design background, I find toilets so interesting, because there's so little design there. They're kind of massively neglected by designers, by politicians and policymakers. Like in the most basic terms, just getting in the cubicle can be quite difficult. And then there's the ergonomics of it like pulling your shoulder trying to reach the toilet paper, but then it just kind of proliferates into communication design and wayfinding and service design like the system the order in which you go through the steps to use a public toilet. Have it then fits into the built environment and accessibility and how we move around our citizens our lives. We just find endless ways to look at and research into design through this lens of the public toilet.

Jo-Anne 04:56

Yeah, it's like a petri dish for all kinds of inclusivity. Every aspect, as Gail said, you know, you get into product design, you get into architectural and space design, you get into service design. And if one element of those features fails, the toilet will fail. So, you know, you can have a toilet paper dispenser that can't be actually used by everybody due to hand problems and reach problems and other ergonomic issues. But then, if there's no toilet paper in the toilet paper dispenser, then that's a major service design failure in some ways. So it's kind of a very sort of narrow perspective, but it can be so widely applied to all areas of inclusivity and inclusive design. One of the things that kind of makes me laugh, makes me smile, is that when people come and sit by us in, in our research studio, we tell them, look, we've got to warn you now all we talk about is toilets. And they're like, Oh, you must talk about other things, you know, life this, that and the other. It's like, No, we don't, all we talk about is toilets. And people do come and sit with us. And they're working with us for a few months. And like it's true. All you talk about is toilets. We talk about them constantly. We we find, you know, a news item comes

up and we'll be sharing it with each other, we'll see a toilet angle to it, we'll go into long conversations about locks and about doors about, about every aspect. And getting into the politics, the policy, what's bad, what's good, I saw a really great toilet the other day, really bad toilet the other day, you know, This all helps to feed into what we are considering good design of toilets and bad design of toilets, and how we're going to try and not replicate, or maybe use that as a lesson to take forward.

Gail 07:00

It is also a really useful way to explain my job to people, like parents on the school run, can start talking about inclusive design and social challenges. And they glaze over and have no idea what I'm talking about. And I say for example, most of my research is about public toilets. And then they instantly think I'm a bit weird. But then, as Jo-Anne said before, they have their own toilet experiences, because everybody does. So they'll start either talking about a great toilet that they once saw, or this awful toilet that they went to last time or quite often they start opening up and talking about their own personal experiences, because they have irritable bowel syndrome or older parents that they need to look after and say actually, they don't leave the house unless they know that there's somebody that that they know that they can use. So it becomes this, I mean, it's a great subject matter to be able to sort of do inclusive design ad hoc, just constantly learning more and more experiences and angles to it.

Benji Jeffrey 07:55

And it's also I think, as creative as quite often it's quite difficult when someone asks you what you do to kind of boil it down to just to have something that's just one word. And also that something that has a lot of baggage, right, as something to do with accessibility. You know, there's quite a kind of serious side to it. But at the same time, you know, it's also hilarious. Toilets are very funny things like toilet humour is a big thing.

Jo-Anne 08:16

Yeah, yeah. I mean, it's very much embedded within our culture, in British culture, about toilets, you know, and, you know, we have certain historical pride that we were one of the first cities to, you know, especially in London to have public toilets. And, and, you know, in the UK, we used to have a really huge public toilets map, of toilets in every city, it was a, you know, a marvel of Victorian philanthropy that every town would have a toilet, you know, and now, when sometimes people complain about toilets, you know, well we once lead the way in this. And now, you know, And now where are we because we are losing them at an alarming rate. And we are both passionate about the fact that there does need to be more toilets, but also, we've got to find new ways of providing that service. Because for many local authorities, you know, they're faced with such serious budget constraints that sometimes, you know, reluctantly, they have no option but to close the toilets, because, you know, they're quite expensive to maintain, especially when you think of some of the other activities that take place in toilets, especially vandalism. There's a big problem with vandalism at the moment. And so, building robust public toilets that are able to withstand a little bit of frustration is also really important, but it's also really important to make those toilets accessible. So you're bringing this sort of like 'designing out crime' element with Inclusive Design, and making sure that one doesn't cancel out the

other because in most toilets that have been built and designed from a resistance perspective to withstand some of these activities, the inclusion the accessibility has just been designed right out.

Benji Jeffrey 10:07

Right, because I guess in London a lot of the public toilets are underground. Yes, to an extent, right? So not accessible for everyone.

Gail 10:15

Yeah. And it's gone through these different cycles of replacing the underground toilets with automatic public toilets, which were then street level and much more accessible because they could be used by wheelchair users and have been changing everything built in and they were self cleaning.

But then that didn't work because they just want to make a good design that people don't want to use an automatic toilet where you need to, as someone Jo-Anne spoke to said, like, you don't want to have to read instructions on how to use the toilet, and you don't the door to open on on the street, if you if you get it wrong. So then those are taken away, and then you end up with well, now we haven't got anything.

As you said before, that we have this culture of finding toilets very amusing. Like it, it's got two sides to it, because we are starting to use that a bit to have better puns in our work. I was always very uptight about it. Because it's a serious issue, you know, this is affecting people, it's really needed to be taken seriously and not made jokes about. But actually, it's quite fun. So now we have a website called TINKLE, which is The Toilets, Innovation and New Knowledge Exchange, of all the resources that either we've made or other researchers or organisations have made about UK toilet design.

And then our last project, which is called Engaged, one of our researchers said that it's as if we're trying to create Loo-topia on the high street, perfect public toilets. Now, we really want a project called Loo-topia. But I do feel that this taboo that exists alongside that of like, we can joke about toilets, but we can't raise them in a meeting, we can't like, we're too embarrassed to actually talk about toilets is a real problem for the UK in getting a better quality of public toilets. Whenever I'm looking at government documents, inclusive design guidance, information, 50 ways on how to improve your high street, there were dozens of these reports out there, and they don't mention toilets. And it's so obvious once you start thinking about it. But instead they'll talk about the hanging baskets, and the free parking and the benches, or they'll talk about “accessible facilities”, but they won't specifically say you need to have a toilet, or else people can't spend more than half an hour or an hour on your high street. But if you don't mention it, then the designers aren't going to catch on, or they're gonna think they're being a bit weird by bringing it up in a meeting like it doesn't, it doesn't help facilitate conversation, and it doesn't sort of bring it to the table. So finding that side of the British toilet humour is quite a big challenge.

Jo-Anne 12:34

Yeah, I mean, we were - there was a cycling... Gail's a very keen cyclist. And there was a new cycling policy document that came out and we sort of like, oh, this is interesting, we went through and we did the word search, and of course, nothing, nothing about toilets. And cyclists need toilets, you know, they, you know, they, their journeys might be slightly shorter, or slightly longer than the average car driver, or even van driver or, but they still need toilets on the journey. And people, you know, pedestrians, obviously, you know, people decide to walk from one station to another station and avoid public transport or something, you know, at some point along the way, they might need a toilet. And often people are sort of really reluctant to go into a business where they don't have to buy something, to use the toilets, you know, there's, there's this, it's almost like this, we kind of sort of infantile people by sort of, like, you know, getting them to sort of like, “Can I use your toilet please?”, we shouldn't have to ask to use the toilet.

So there's been lots of initiatives, some of which have worked, some of which haven't worked to open up, sort of private space shops and cafes and everything to let non customers use their toilets. But I think we're still somewhat nervous about going into that private space where we don't feel that we have an automatic right of access to a toilet and actually using it. And obviously, with that, the owner of the business always has the right to refuse. And, that's their right, it's their business. So it doesn't mean that everybody can actually have access to toilets. And that's why public toilets are still really important.

Benji Jeffrey 13:13

And there's two different strands going on there in what you're talking about, right? There's the design element, which is designing the correct toilet, and then the kind of cultural policy side of things. Do you get engaged in the policy side of things as well as the design side of things?

Gail 14:31

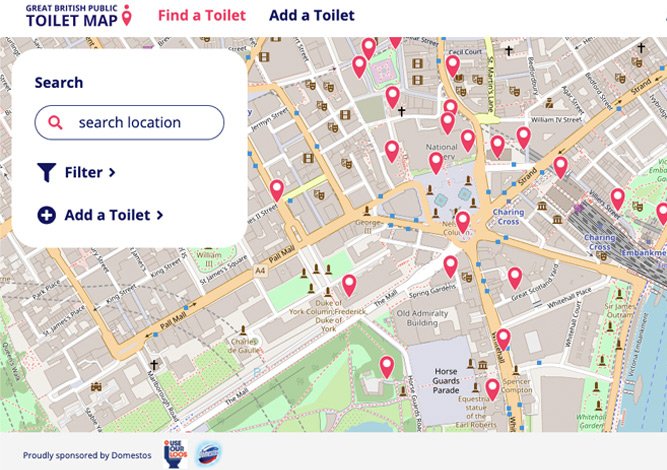

Yeah, because I think the policy side of it, it sort of reflects the systemic design, like the barriers that stop more toilets and better toilets being built in the first place. There's no policy that says councils have to provide toilets. And so there's no money to support councils in providing toilets, and if they're not, haven't got the money to build them or to refurbish them, then how are we going to help them to make them more inclusive? So just finding out where the toilets are is a big problem which is why we made the Great British Public Toilet Map, which is a UK wide database of all the publicly accessible toilets that we now have in the country. So public toilets, but also ones in train stations and shopping centres and anywhere that the public does have a sort of right of access. So there's 14,000 of those. That was one problem of just knowing where the toilets are that already exist. And then once we know, we can also try to share the design guidance that we have in how to make toilets more inclusive. So we've done some consultancy work there too, yeah, trying to get the best standard of toilet built, but it's definitely a very broad subject. And we do like to tackle all sides to it.

Benji Jeffrey 15:39

And you touched on TINKLE earlier as well. Can you tell us a bit more about TINKLE?

Gail 15:43

So TINKLE is a website where we have pulled together all the UK design guidance around toilets. We also have a list of toilet design experts, and a blog element to it that we call Latrinalia, which is the term used for toilet graffiti. But we were using it for a kind of online, peer to peer community. So yes, that's it, it's quite... toilets are quite a niche subject. But as Jo-Anne was saying before, with cycling, they affect so many different aspects of life, like commuting and cycling and accessing nature and tourism and public health, so they don't fit within any one person's job description or department. So they do fall between the cracks, no pun intended.

So, yeah, it gets overlooked a lot. And that happens again, with the guidance that is out there. But there's, you know, British Standards about public toilets that people don't know or find out about, and Jo-Anne's on that standards committee. So it's a brilliant standard. But if people don't know that it exists, and they didn't know that they could be following it. Network Rail recently wrote a massive document about the inclusive design of toilets in their stations, and they've done a lot of work, refurbishing all of their toilets, and removing the charges, even though they're making a fortune out of charging people for you to pay to use the toilet. And they're now building towards a really high standard with a massive document to go with it. So all of these things exist. And we know about them, but we don't know if other people know about them. So if you pull it all into one place, we can help particularly designers and architects to find out the best standards for building toilets.

Benji Jeffrey 17:18

And is that what TINKLE is? Brilliant. With all these kinds of possibilities for how things can be changed, do you perceive that there is any sort of limit to the capacity for inclusivity within this?

Jo-Anne 17:33

Well, once upon a time, I mean, it wasn't that long ago, maybe 15 years ago, when we first started doing the research, there were people with profound multiple disabilities, they weren't really catered for by the accessible toilet. And there was a group in Scotland called Pamis, who put together and designed what they called a changing places toilet that included an adult changing bed in it and much larger space. And, you know, initially that was quite niche. But now recently, the government put I think it was 30 million, wasn't it 30 million funding in place for, you know, changing places, toilets to be built everywhere.

And they actually have their own separate map, although we do include them on the Great British Public Toilet Map. And they aren't, they now should be found at changing places toilet should be found in you know, basically, every city, lots of museums are building them. And they're becoming a more common feature of toilet provision in the UK. And I believe, you know, that's something that we can say, once again, in a toilet pride of a country that we are leading the way in that we're providing, you know, some very, very important pieces of toilet infrastructure for those who are very, very, disabled and need extra care, extra space, more people to help them within the toilet provision. But there's also other aspects, so we're thinking about things like neurodiversity, and areas such as that, you know, these are pretty new areas to think about in terms of design for the built environment.

Our colleague, Dr. Katie Gowdy, and she's doing a lot of work in that area. And we do hope that we can join up with her soon and she's just finished a work, some work on streetscapes, and we're hoping that we might be able to turn that into a more sort of active toilet research project that looks at what are the needs of our neuro diverse population when it comes to toilets. I mean, I know from my previous research that a lot of people with neurodiversity found the blue lights that were very common about 10 years ago, which were a design-out crime intervention to stop intravenous drug use in toilets. But this blue light actually made the toilet environment very unwelcoming for you know, for people with visual impairments, for older people who found it just very overwhelming, and especially for people with autism and who are neurodiverse, who also found it a very, very alien space to be inside. So looking more at that area, those are sort of new areas that need more thought and attention, I think.

Gail 20:20

Yes, certainly, hand dryers are another one that comes up a lot - children with autism can be very kind of distressed by the noise that comes from the hand dryers, the new ones. So there's elements to the physical product design that can be improved with more awareness of neurodiversity. Katie and I have also been talking about other aspects of the toilet, such as the full sensory experience with the toilet, there's lots of different smells going on. And but there's also ways to mask smells, and that those themselves can be overwhelming. So it's sort of figuring out what the balances of what will be, there is almost never a one size fits all solution, but increasing the awareness of different people's needs before making these decisions. And then there's also kind of a social aspect to toilets in that, as Jo-Anne said earlier, everybody needs to use the toilet, and there'll be complete strangers with very different needs and very different preferences using the toilet at the same time. It's a scenario where all different parts of society come together and maybe don't appreciate or aren't empathic to each other's experiences. So is it a setting for where the experiences of people with different disabilities or people with neurodiversity could be elevated and shared? So that that kind of mutual understanding is enhanced?

Benji Jeffrey 21:43

And do you think that is possible to be? It just seems so utopian right to have this magical, sorry, loo-topian, to have this magical space that is able to cater to everyone? Can you see that happening?

Gail 22:01

It's possible. But yeah... yeah.

Jo-Anne 22:04

I think design, design has all the possibilities, don't think we've got all the answers yet. And good design research and, you know, that will help good design can make these things possible. I mean, what could the future toilet be? Possibly a self contained cubicle that you somehow set the ambience to that you control the ventilation in, in some way, shape, or form? I remember some researchers from the Netherlands did this design of this toilet that would come with an access card, and all your preferences would be on this card, and you'd swipe it in like you would your Oyster card, and the toilet would reconfigure itself to how you needed it. And it was brilliant. But the reality of it is, is that no one's going to pay for that. That's a very, very expensive high tech toilet to actually produce. So how can we take things that we learned from those research from that research, and sort of like make it more static, or what learnings are there, I mean, it could be that as technology becomes more prevalent, you know, that things can be made a lot cheaper, or a lot more sustainable, or a lot easier to maintain, and service and clean, because that's the other element of the toilet, we know we can all go in there and use it. But someone's got to come in and clean it after us. And we really want that sort of, we want, we want to know that our environment that we're going to get down and dirty and pardon the pun, is going to be clean. And the next user, you know, won't be able to sort of sense that we've already been in there - it’s an incredibly private act in public. So what kind of technologies do cleaners need, you know, and these are the other people that we, you know, we try to involve in our toilet sort of research to find out what works for them. Now, there are some aspects of toilet design that work better for them, but don't really work for users. So you know, what's the balance, it is finding a balance between every possible person that's going to be in there, and then doing it in a cost effective way.

Benji Jeffrey 24:14

And you touched on sustainability there as well. What are the concerns of sustainability in this because surely, as well, this inclusive toilet, does it become less sustainable by trying to by needing cleaning more often and needing more facilities in it? Or? We're talking to this utopian toilet?

Jo-Anne 24:35

Yeah, it's difficult. I mean, there's been lots of technologies that have been introduced into toilets that have and have not worked. So some have tried to use gray water for flushing. You know, some have tried to use like, you know, the short flush and the long flush, which I personally don't believe works in public because people want to get rid of their waste and nobody wants to see evidence of but I went to Japan once and for the Kyoto agreement, way back when, they built a fantastic sustainable toilet, it was gray watered, and it was, you know, light censored. So the lights only came on when the user was in there. And they had even produced water recycling sort of aspects of the flushing as well. But what they couldn't do was like, get the water clear. So the water was yellow, even though it was clean water. And, you know, you walked in, and you just saw this yellow water. And of course, your immediate thought was that somebody had used it. And that, you know, so a sense of a stranger has been there before you and hadn't flushed all these thoughts going on with that person is... you know, you know, it just feels icky. So, but they, they, you know, the designers assured me that, you know, that's just it, we just cannot get the yellow out of the water. So I found that really interesting, because then we're getting into this sort of personal cultural sort of element that's sort of mixing with the desire to be more sustainable and use our resources more wisely. But in some ways, we're just not there yet. You know, sometimes we've got, we've got a little bit more to go to actually sort of sort these things out, which are, you know, sort of personal, social and cultural phobias that we experience in the toilet, we don't experience them at home. But the minute you know what, what goes on in our own homes, we've got a very, very relaxed sort of attitude towards. But when we get into public space, we've got this layer of public-ness that comes on to us. And there's a whole different criteria that we have to engage with, when we walk into the toilet cubicle.

Gail 26:49

With the app, what I find interesting is that there are these cultural elements to it that stop people from changing their behavior, even if it's a better design, like there are some places in the city now, but much more in the countryside where you'll have composting toilets. And that compost waste can then be reused. There's one in an allotment in East London. So that can proliferate. And as people get more experiences of using things like that, then there'll be less confusion by the next time. And another area where there's social and cultural norms is the idea that we need separate genders of toilets. And that giving up the separate genders of toilets is somehow against British culture or something like this is sort of an arbitrary distinction that we should have men's and females toilets, rather than just having private toilets, where it doesn't really matter who else is in the space, because we've got our own cubicle to do whatever it is that we need to do. And there are lots of reasons why people might want more privacy than the standard cubicle. toilet cubicle design offers them saying, we kind of Yeah, trying to encourage the best possible most inclusive toilet design. There's lots of barriers in the way. And sometimes it's the sort of practical maintenance engineer. barriers of thought, This is how we've always made them. And this is the cheapest way to do it. So why should we do it any differently, but sometimes it's much more cultural or social, which makes it interesting for us.

Jo-Anne 28:10

I mean, one of the things that Gail and I did was we did a consultation for a museum in London, and they were building fully enclosed cubicles, and they wanted them to be gender neutral. And we took a cue from the Alzheimer Society, who in the signage for the toilets, that instead of putting a figure of the user on the toilet, which automatically reminds the user who has the right of access, we just put a toilet on the door, just a picture of the WC pan.. at the end of the day. It's a toilet. Yeah, that's what it is. That's what it's there for. And as far as we're aware, they've gone down very, very well. And, actually, we also recommended that to the RCA when they were building the research tower, which we now sit in, and they've done the same here. And we have received comments from visitors saying we like the signage for the toilets, because at the end of the day, it's a fully enclosed cubicle. It's, once you get in it, it's yours. It's your cubicle, and it's a toilet, and you're doing what you're doing in there. And then you leave and the next user comes in, and it becomes their cubicle after you. And there seems to be, you know, some of the issues that arise from this because it's about privacy at the end of the day. What people want when they use the toilet is privacy. And so we feel that just having the sign of a toilet logo kind of takes away some of those other issues that sometimes make our life very interesting.

Benji Jeffrey 29:48

I think there's lots of examples on the web. That doesn't happen for practical reasons that we forget like festivals, for example, right? It's very rare that you have a gendered door at a festival. but also to say you always remember a good toilet as well. Yeah, like the British Summertime thing in Hyde Park that happened this year. The toilets were phenomenal. They were like space age toilets like that rather than your kind of standard kind of blue dingy, they had beautiful lighting - great for selfies. They’ve become a really exciting place to be!

Jo-Anne 30:20

Yeah. Yeah. And, and that, I mean, this is something I think more and more people who are into experience design, realise that, you know, if you're designing for humans to be somewhere for more than maybe three or four hours or maybe more, even more than two hours, you're gonna have to think about somewhere for them to go. And, you know, if you build that toilet into the experience, then, you know, people are gonna remember that toilet. Remember, we all have good toilet stories. And we all have bad toilet stories. So, you know, having a really good toilet that people are going to say ‘oh, you know, we went to that great festival, but the toilets were bloody brilliant. They were so much fun. They were this or they were that’, you know, it really helps embed that memory. And that creation of memory, and people will come back. And it's the same for any kind of business. If you spend time and attention on making your toilets interesting and accessible, they have to be accessible, you know, people will come back and they will remember your toilets.

My mum once took me to this place in Spain (my mum lives in Spain) and she took me to this town Murica. And she said, we have to go to this casino in Murcia - the casino is like the Working Men's Club. And she said we have to go there because the toilets are just fantastic. And they were they were the they were the women's toilets. It was like an art gallery. There were frescoes on the roof. And it was beautiful. And you know, it's like, it stays in people's memories. And then people actually want to take people to that. Now, there are two countries that have actually sort of capitalised on this fact, New Zealand and Japan, who have actually built some really, really interesting toilets that themselves have become Placemakers and have become places that you know, oh, we'll go there. But we've got to see the toilets as well. They actually become part of the tourist trail and everything. And that's something that I think London could really capitalise on and and a lot of small towns as well.

Benji Jeffrey 32:27

Becoming the toilet capital of the UK should be the aim. So the two of you make up the Public Toilet Research Unit. Is that correct? How does that work within The Helen Hamlyn Centre? Because there's lots of other researchers working on different topics. Are you working with each other on that? Or is it quite independent? How does it work on a day to day

Gail 32:48

Now we all work together when we can. So the Public Toilet Research Unit is a neat way of putting together all of the work that Jo-Anne and I have done, and other researchers that work on projects have done around public toilets. But we also work within the inclusive design for social impact space. So, as you mentioned in the intro will have projects working with communities and citizens around different social challenges. So in the past, there's been projects around childhood obesity, for example around a housing estate in South London. So in the public toilets, research units, our last project was called engaged and that was funded by the Mayor of London on a programme called Designing London's recovery. So looking at ways to innovate in London post pandemic. And that looked at the idea that maybe empty shops could be used as part public toilet part business. So something between the standalone public toilet and asking shops to let non-customers use their toilet, maybe councils could have a role in bringing more toilets to the High Street in this sort of protected space because there'd be a business there as well within the retail unit. And they could have more say around what that toilet design would be. So make sure that it is an inclusive toilet and make sure it's meeting unmet needs within that community. So that was really interesting project. And we had other researchers within the Helen Hamlyn Centre, who had worked on in many different areas of the Helen Hamlyn Centre, could then come on to that project, and then all about toilets, which they were really, really excited to do with anybody they were like 'this is amazing'.. so much that we can talk about. Yeah, so that project was really interesting to just learn more about the barriers from Council sides as to how to get things happening. We talk to a lot of regeneration officers who said that they sort of bring in the money and the ideas into the council, but then it gets moved on towards sort of practical elements of planning and design, and developers and finance. So whilst the community at the start of regeneration projects will almost always say that they need toilets within their local community and it's something that they can very easily get the community excited about. It can often get forgotten about on what can be like a five to 10 year process. So one way that we could make a difference is finding ways within councils to keep toilets on the agenda, figuring out how to have someone responsible within the Council for toilets, getting the counselors to have toilet strategies, which is something which is the law in Wales, the Public Health Act in Wales said that all councils have to have a toilet strategy, but it's not something that's happened in the UK, so we could do more research around the benefits of those and if there's a way to promote them within the UK. So it's, it's interesting how kind of specific an idea can get. But that is where we can make the most difference in a way not with the big ideas, but with figuring out what the barriers are, and mechanisms for getting around them. So yeah, within the centre, we tried to get as many people involved in toilets as possible.

Benji Jeffrey 32:55

And do you find that people come to kind of get consultation from you as the experts in toilets?

Jo-Anne 35:56

Yeah, yeah, I mean, we also do have our own sort of RCA spin out business, Public Convenience Limited. I mean, it really is all Gail and I talk about... we do, we do offer some sort of consultation through that. And we have done some work on that with local authorities and London sort of organisations. But they also come to the Helen Hamlyn Centre, every now and again, sometimes with some ideas that we then have to slowly let them down by saying, well, it's not really inclusive, or it's thinking about that and thinking about that, you know, some people have some great ideas about toilets and how it worked well for grandma, and it should be like in the market. And we can say, well, you know, unfortunately, that's really not going to work for the markets.

Gail 36:46

That's the great thing about inclusive design, like both for businesses and for the students is that it can feel quite laborious trying to involve people in a process when you just want to get on with your design. But it's always so rewarding to hear people's first hand experiences, hear that diversity of experiences, but also where they're having the same struggles. And you as a designer can think, hang on, I can do something about this that can really make a difference in people's lives. And also just to challenge your own assumptions that you think you have all the answers. And then it turns out, you just you've never looked at it from that perspective before. Yeah, things like colour contrast, I'd never thought about before coming to the Helen Hamlyn Centre, and thinking, Oh, actually, people with visual impairments would see the toilets much better if you just had the tiles on the wall a different colour to all of the fixtures and fittings, like why is everything white and reflects reflective, you think it looks clean, but it's actually just quite kind of overwhelming for a lot of people to interpret that space. So yeah, big fan of inclusive design.

Jo-Anne 37:44

The other, I mean, the other thing as well is that sometimes you can be talking to a very, very diverse group of people that you think, you know, initially, there's no sort of parallel, and there's no common ground between them. And yet you talk to them. And you suddenly find out that this group over here, who had these specific needs, and this group over here, have these specific needs actually have this one singular need. And in many ways, that's how the Great British Public Toilet Map was born. You know, it came from the fact that, you know, lots and lots of people have very, very differing needs had this one singular need, which was a lack of information about where toilets were. And so that's how it happened.

Gail 38:29

If you can provide the information, then they can determine whether or not it's a toilet that meets their specific needs, but at least they know it exists. Yeah. And they're the best person to determine if you'll see them.

Jo-Anne 38:39

Now designers love challenges. So talking to people who have a range of very different needs, which at the beginning might seem oh my goodness for house, you know, we're never going to see the wood from the trees will actually show that there is a probably a common theme that fits for them, but also actually fits for the rest of us as well.

Benji Jeffrey 39:00

What's it called? A ‘disability gain’? I believe that’s what it's called - I remember someone telling me about that. It's like when when there are subtitles on something, that they're there for someone who can't hear, but actually they’re useful for people that that are able to.

Gail 39:14

Having that different colour contrast in the toilets at the museum where we're working, giving some consultation advice, like that just makes a much nicer invite for everyone, because then you've introduced colour into the environment. Yeah, and there's lots of other ways that we recommend making a toilet more inclusive, such as having larger taps or locks or flushes that can be used by people with arthritis. So if you could use it with your elbow or closed fists, then you know that it doesn't need a high level of strength or dexterity to use it. But then when I go with my six year old, she can also unlock the toilet as well. And so it's just kind of seeing things from other perspectives to realise that actually, that's just a better toilet. That's just a better design for for everyone.

Benji Jeffrey 39:52

Yeah, I'm afraid I could talk to you all day, but I do have to start wrapping things up now. And I just wondered if you had any advice for people who want to engage broadly with accessible design or even more specifically toilets?

Jo-Anne 40:07

I suppose the first thing well, you know, is to contact Gail and I, at the Helen Hamlyn Centre, especially specifically about toilets. If you have a more general inclusive design, maybe you're thinking about health care or architecture business, we have researchers working in those areas. So just contact the Helen Hamlyn Centre, and there'll be someone there who will be willing to take you through your first steps and talk to you more about it. So yeah, that's just a, you know, another plug. You can also if you're hesitating to contact us, you can wait for the release of our book to be released next year. It's called Designing Inclusive Public Toilets with a subtitle ‘Wee the people’.

Benji Jeffrey 40:55

Is that W-E-E?

Jo-Anne 40:55

It is yep, and it won't quite be a manifesto, but it will be available from Bloomsbury in 2024. Fingers crossed.

Benji Jeffrey 41:07

Exciting. What about you Gail, anything that you would recommend?

Gail 41:10

Well for inclusive design in general, The Helen Hamlyn Centre runs a series called Design.Different. So every couple of months, there's a new webinar that anybody can sign up to, it's free. I think it's also recorded so you can catch up later and each one is on a specific aspect of inclusive design, health care, social design and the built environment. Yeah, we've probably done about 15 already.

Benji Jeffrey 41:31

Amazing. You've been listening to the Royal College of Art Podcast, home to the next generation of artists, innovators and entrepreneurs, and the world's number one art and design University. You can learn more about our [email protected] as well as finding news and events relating to the College and our application portal if you're a prospective student.