ADS9: Land–ing

Jump to

From 2024/25 onward, ADS9 will focus on land by challenging architecture’s indifferent relationship with the land. The studio’s investigation centres on a simply stated, but complex design question: How does architecture touch the ground?

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Appropriate Proportion, 2002. Photo: Iwaan Baan

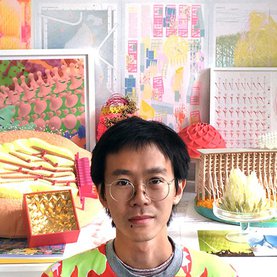

Studio Tutors: John Ng, Zsuzsa Péter & James Chung

Floor screed

Vapour control layer

Rigid insulation

Concrete slab cast in situ

Damp proof membrane

Sand blinding Hardcore, crushed and compacted.

In an act of indifference, architecture is typically created by levelling land to create a limitless zero-degree flat line. The conventional seven-layered concrete ground slab, the beginning of most contemporary architecture, requires a compacted ground that rejects any presence of water and organic matter. In architectural representation, land is abstracted in plan as a thick orthographic line that denotes ownership and political boundaries. In section, a smooth 0.7mm baseline represents an idealised ground plane that separates architecture from the blank space of the paper sheet. Land is abstracted to a generic entity that is devoid of physical properties and an ability to illustrate the transformations of the ground.

In 2023/24, ADS9 concluded our seven-year investigation into the architecture of openness; an investigation that questioned our fundamental dependence on walls to define space. From this year onward, ADS9 will focus on land by challenging architecture’s indifferent relationship with the land. The studio’s investigation centres on a simply stated, but complex design question: How does architecture touch the ground?

Walter de Maria, The Lightning Field, 1977

Land

In Pichátaro, Pátzcuaro Basin, Mexico, land is viewed as a living entity and the mother of all life. This indigenous notion of land combines Meso-American beliefs with Catholicism, creating a belief system that emphasises the interdependent relationships between land, living things, and humans, as essential for sustaining life. Although economic and environmental factors may challenge such a belief system, human interventions in land care and farming are vital for survival of the system. The land is seen as an interconnected whole; encompassing water, climate, and soil, and demanding a respect and careful stewardship to maintain its role as a life-support system.[1]

Land, ground, territory, crust, field, motherland, landscape, terrain, environment, city, sprawl, ecology, earth, and Earth. Land is space. It is also a physical space of material and expansive transformations. It is a terrain of consciousness related to a place and the ideas which have developed about how to live in that place. [2] Land is not an empty space. It is not a postcard picturesque state of innocence. Land is disrupted and denaturalised.

Looking in close–up, the ground on which architecture is anchored is never a solid homogenous mass. Broken-down rocks, sand, silt, and clay have been formed into a subtsance that has structural and functional integrity; working like a sponge to absorb rainwater and, in urban environments, collecting all the residues and by–products of human habitation. Ground and soils are less layers and resources, than bodies and processes that are without clear boundaries, formed through the interactions between mineral, biological and human interventions.

Looking at the expanse of the territory, architecture and forms of living are defined by the natural limits of land. There is an empowerment and knowledge to be rediscovered in the historical and generational understanding of land and how it shapes the way we inhabit space. How do we project this forward to include the uprooted? The wanderer? The global cosmopolitan and future generations yet to come? How do we extend this understanding beyond humans to include the rights of all living things?

Our project begins by searching for forms of land as context. ADS9 asks students to determine on a scale of land to investigate, from looking in close –up at land and its material composition, or by expanding out to a territorial scale. By looking down, looking across, surveying, measuring, and indexing land, the search and research will be compiled into a dossier and set of large drawings. Following the Pichátaro’s understanding that the land is a complex and ambiguous interconnected whole, each student will be asked to develop an understanding of land through a comprehensive study which covers forms of living, (hi)stories, meanings, processes, politics, and the economy. All the whole, attempting to comprehend how these forces are embodied within the physicality of land and architecture.

Space X, Falcon 9 landing, 2016

Landing

‘Appropriate Proportion’ is a reconstruction project by the artist–designer Hiroshi Sugimoto. Go’o Shrine, on Naoshima, Japan, dates to the fourteenth century. Sugimoto reimagines the shrine following the inspiration of natural ‘power places’, like the sacred giant rocks revered in Shinto practices. Sugimoto’s design centres on a staircase made of rough-hewn optical glass steps. The point of contact between architecture and land touches down with a dematerialised heaviness. The incongruity of a glass stair is visually defiant; it is a delicate and fragile sewing along the monumental axis that connects the earthbound Rock Chamber and Worship Hall to the celestial realms above. [1]

In parallel to searching and researching forms of land, ADS9 will focus on architectonic experimentations of how architecture touches the ground. An individual architectonic language will be developed through a series of experimental prototypes. Mobilising land as a verb, ADS9 will put forward a provocation of how an alternative architectonic language can re-examine the relationship between architecture and land, and, by extension, the relationship of humans to something greater than the sum of us all.

Can you imagine an architecture that uncovers and exposes land in all its raw glory? One that anchors and secures itself onto something deep? One that crash-lands and sets down in defiance?

One that plants its feet in a firmly deliberate gesture? One that stomps and squats with a heavy, forceful impact? One that touches lightly with a barely there contact? One that settles over time? One that sinks into a slowly opening negative space? One that drops with a casualness? One that presses, balancing on an incline? One that is a gentle, light, graceful, fleeting contact? One that is rooted? What does each one of these gestures say about the architectural relationship with land?

Once distances exceeded a certain limit, it was impossible to determine these distances from sight alone. [2] Geometry and geometric methods of measurement have become indispensable to understanding and operating in larger territories through surveying, the art of measuring, and establishing the relative spatial location of points on, or near the surface of the earth to determine the terrain of the land. Surveying is the translation of the land through an abstract, homogenous mathematical space. New technologies allow us access to accuracy, but also the possibility of selectively deciding what and how it can be measured without the necessity of deferring to a unifying method. New cartographies that combines types of surveyed information will be the basis of establishing how our architectural proposals relates to land.

Diana Scherer, Exercises in Root System Domestication, 2015 - ongoing

How Do We Experiment and Design?

ADS9 has a deep commitment to space and creating architecture that is imbued with an urgent beauty. Space does not simply frame – it is inseparable in how we express, embody, and enable knowledge, ideas, and life. Spatial experimentation is at the forefront of the studio’s methodology. To experiment is to embrace the desire and beauty in the act of creating itself, regardless of where it may take you.

ADS9 experiments with large-scale media, tools, and prototypes that are spatial constructs in their own right. It is a highly iterative process which critically questions design. It is a way of design that goes beyond a representation of the subject to have a hands-on direct engagement with your topic of spatial experimentation. As part of your personal development of spatial experimentation, ADS9 encourages students to reach out to the full arsenal of knowledge, expertise, and tools at your disposal across the different departments aoft the RCA.

The design project will focus on a building with a minimum area of 5,000m2. For YR1, the spatial experimentation will be accompanied by technical investigation. In ADS9, YR2 students have always pursued deeply personal subjects and obsessions in their work. The design project is open to the ambitions of our students. In response, YR2 students will develop their own personal critical framework and design methodology to achieve a high level of architectural resolution.

Just remember, 'No Brown'

Notes:

[1] Barrera-Bassols, N. and Zinck, A., 2003: ‘Land moves and behaves’: indigenous discourse on sustainable land management in Pichátaro, Pátzcuaro basin, Mexico. Geogr. Ann. 85 A (3–4): 229–245.

[2] Peter Berg and Raymond Dasmann ‘Reinhabiting California’ in Cheryll Glotfelty and Eve Quesnel (Eds.), The Biosphere and the Bioregion: Essential Writings of Peter Berg. London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015.

[3]https://www.sugimotohiroshi.com/appropreate-proportion

[4] Hélène Vérin, ‘Technology in the Park: Engineers and Gardeners in Seventeenth Century France’, in Monique Mosser and Georges Teyssot (Eds.), The History of Garden Design: The Western Tradition from Renaissance to the Present Day. Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, and MIT, 1991.

Tutors:

John Ng has been an Associate Lecturer at the RCA since 2017. He studied architecture at the University of Bath and the Architectural Association, where he has taught since 2011. He founded ELSEWHERE and practises architecture in London. His work has been shortlisted for, and has won, a number of international competitions.

Zsuzsa Péter graduated with Diploma Honours from the AA in 2018. She is an Associate Lecturer at the RCA, while also teaching in Studio Díaz Moreno García Grinda at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. In recent years she has collaborated on several projects with amid.cero9.

James Kwang-Ho Chung is an Associate Lecturer at the RCA, a Diploma unit master at the AA and a programme head of the AA Visiting School Seoul. He has taught extensively in numerous design studios and has given lectures at various academic institutions in Korea and the UK.