Key details

Date

- 2 June 2025

Read time

- 5 minutes

In a time of rising political and social pressures, queer, trans, and femme communities are using art as a powerful tool for resistance, celebration, and connection.

When it comes to disrupting normative power structures, occupying physical space is everything. It’s inside the sweaty club, on the streets of a protest, or even in the gentle fold of a book reading that ideas and stories are shared in real-time, face-to-face. Queer activism thrives in these spaces. It is here, in the heart of tangible moments, that visibility, resistance, and solidarity come to life.

Art plays a central role in this process—particularly for marginalized communities. Whether through performance, architecture, or collective events, art creates platforms for self-expression and pushes against societal norms.

Creating Spaces of Freedom and Community

For Lucy Nurnberg, who graduated from RCA’s Interior Design MA and uses art to forge spaces where queer, trans, and femme identities can be affirmed and celebrated, the creation of her Mobile Dyke Bar exemplifies this. The bar isn’t just a mobile disco; it is a moving space of collective joy and political resistance. “I’m a big believer in the power of people being in a room together, whether that is to dance, and just to have a silly time,” says Nurnberg. “That is a very political act and it galvanizes something between us as a community to just look around and think: oh, there are other people like me.”

This notion of art as a tool for subversion is echoed by Elinor Henry, currently on the RCA’s Speculative Spatial Design programme, who is working on a film that centers around a far-right theocracy in Ireland that “condemns deviant bodies such as queer, feminist or folkloric”. “It is influenced by George Orwell's 1984 in the sense that the government implements a series of spatial interventions with public-facing narratives aided by technology and marketing that cloak more sinister intentions,” Henry explains. Henry’s work addresses systems of power, oppression and control as being the root causes for this “era of social and ecological crises”, which are being felt deeply across queer communities.

Dr. Mijke van der Drift, a research tutor on RCA’s Animation and Visual Communication courses, articulates this oppression as something embodied. "Right now, trans people say they feel the pressure is rising, and we feel it in our bodies," van der Drift notes. "There are spaces that are welcoming and open, and others where you feel extra pressure." Her new book Trans Femme Futures, written in collaboration with Nat Raha, explores how art can be a platform for resistance, grounded in both theory and lived vulnerability. Van der Drift and Raha emphasise the importance of creating spaces that provide the freedom to explore and live outside of normative constraints.

Interactive seahorse imagined by Elinor Henry

Intergenerational Learning and Queer Ageism

This need for freedom and space extends to the importance of in-person gatherings for intergenerational learning. Van der Drift recalls an experience from a protest at the Department of Education, where younger trans people were amazed to meet someone from an older generation. "They were blown away: 'Wow! You exist. This is possible. This is amazing,'" she shares. The exchange was energizing for both sides.

"There is the bad form of queer ageism, where it’s like: 'There are the dinosaurs,'" she continues. "But the good form of queer aging is to show that it’s nonlinear—you’re constantly learning from each other." This idea of a non-hierarchical exchange is key to van der Drift’s vision of how queer and trans communities can evolve. In an upcoming event—hosted by van der Drift—that celebrates the launch of Against Ageism: A Queer Manifesto by Simon(e) van Saarloos, she hopes the conversation will help people move towards a life that is neither young nor old but “engaged and non-liner”.

This non-linear approach to learning extends to the field of architecture. As Gem Barton, a senior tutor on RCA’s Interior Design MA and leader of the Architecture LGBT+ Academic Champions Network (ACN), argues, "It’s no secret that architecture is one of the most traditional, conservative disciplines. It wears its legacy like a badge of honor—rooted in permanence and canonised knowledge." Barton advocates for a radical shift in architectural education and practice, suggesting that if architecture is to be truly inclusive, it must open itself up to queerness.

“The good form of queer aging is to show that it’s nonlinear—you’re constantly learning from each other”

Tutor for RCA's MA Animation and MA Visual Communication

Barton’s critique is echoed by current RCA MA Architecture student Georgie Grantham, who proposes an "alternative temporal framework" for design. "Architecture sees the plan as a static drawing rather than a lived sequence of events," Grantham explains. "It insists on linearity—anchored by systems like the RIBA Plan of Work—which reflect broader capitalist and heteronormative tendencies." Grantham’s thesis project, Kaleidotemporality, seeks to shift the focus from spatial permanence to temporal design, disrupting the exclusion of queer lives from conventional architectural frameworks.

Grantham’s work also tackles historical legacies of exclusion, particularly in relation to laws like Section 28, a 1988 UK law that prohibited local authorities from "promoting homosexuality" or teaching about it in schools. "My work centers on the belief that time itself can be a site of resistance," she explains. "As part of this project, I’ve been speaking directly with those who lived through 1988—particularly lesbians—while conducting a deep dive into the archives at the Bishopsgate Institute. These voices and records help rupture the neat packaging of historical time and reframe 1988—the year Section 28 was passed—as a locus of queer resistance.”

Illustration from Kaleidotemporality: Towards Queer Time and Space by Georgie Grantham

Joy and Humour as Tools for Organising

This commitment to creating space for queer lives is not solely about resistance through serious political action. Lucy Nurnberg's practice is a testament to the power of joy in resistance. Her Mobile Dyke Bar draws inspiration from past queer activist movements and reflects the creativity and joy found in the toughest of times. "The project was definitely inspired by a lot of queer activist movements of the past. The battles the community has faced have been incredibly difficult and serious, but one of the ways that the community has really rallied and resisted is through joy, through dancing, and I felt like that was a fun way to approach it," she says.

Nurnberg sees joy as an essential tool for survival and activism in challenging times. "It feels like we're in quite dark times again, and I feel like the tactic of joy and humor is really, really powerful. After that Supreme Court ruling, there was an emergency demo, and I was actually surprised by how it felt somehow joyful.”

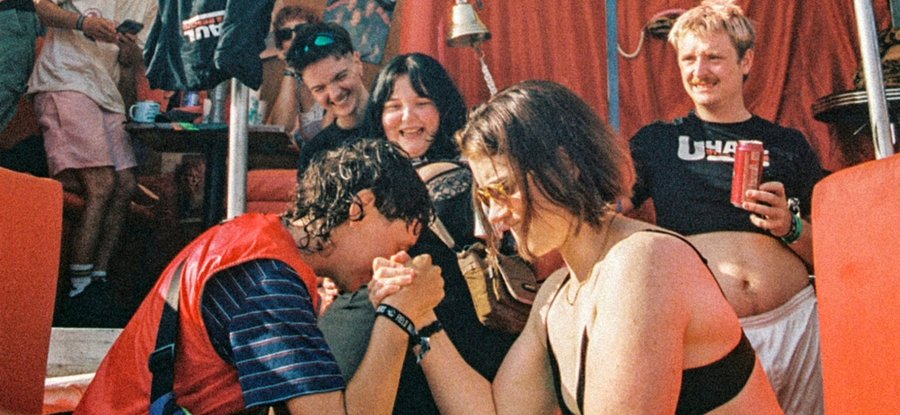

Revellers at the Mobile Dyke Bar

This use of joy as resistance not only challenges oppressive systems but also fosters solidarity within the queer community. Nurnberg’s work is a reminder that activism does not always have to take the form of protest or direct opposition—it can also be a celebration of identity and community, creating spaces where people can feel empowered, seen, and connected.

Van der Drift agrees that activism in art at its best opens up that “sensorium through which the transformation can happen”. “It is literally an aesthetics,” she explains. “It bursts out of you—this sensory and sensual framework—into new possibilities. And I think that is also the possibility of queer life, because it says that: with the exploration of wishes, affects and desires it shows how things can be different.”

Illustration from Kaleidotemporality: Towards Queer Time and Space by Georgie Grantham