Key details

Date

- 28 January 2026

Read time

- 6 minutes

RCA alumni Jasmine Dhika and Tyreis Holder use textiles to explore ancestry, healing and community, weaving memory into new visions of care and sustainability.

Long before textiles became a commodity, it was a language; shaped by land, labour and migration. Today, a new generation of artists is returning to fabric as a way of understanding what has been inherited, and of imagining a more equitable society.

For RCA Textiles MA alumni Jasmine Dhika and Tyreis Holder, making is inseparable from remembering. Their practices – shaped by Indonesia and the Caribbean diaspora respectively – draw on ancestral knowledge not as nostalgia, but as living methodology: a way to heal damaged systems, restore erased histories, and build forms of care that modern industry has largely forgotten.

Holder is an artist, poet and community arts educator from South London whose socially engaged practice moves between textiles, installation, sound and poetry. She describes cloth as a form of language in itself. “I’m especially interested in how textiles function as poetic language – particularly in relation to healing. My work centres on healing within Black women and the wider community,” she says. “I believe textiles speak. They hold identity, generational memory, the relationship between the mind, body and self.”

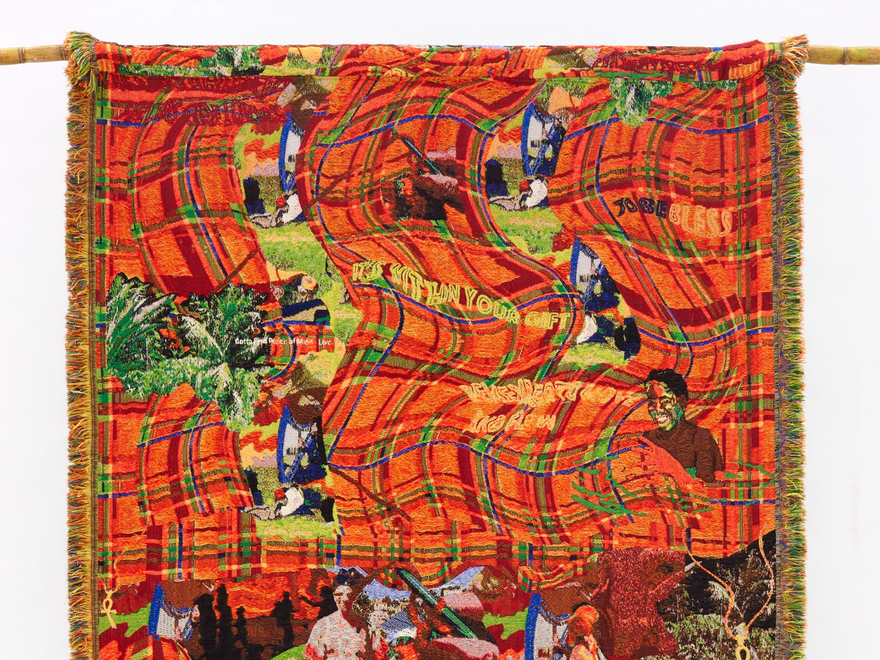

Holder's RCA graduate project, Farìn – Caribbean patois for “foreign” – examined what it means to exist between places, cultures, and bodies.

“Oral history is vital. But textiles are storytellers too. Cloth carries history in its fibres.”

Textiles MA alumna + artist, poet and community arts educator

Dhika, a London-based multidisciplinary textile designer originally from Jakarta, approaches material through ecology and traditional science. Her work investigates how fibres are grown, processed and shared – and what is lost when those systems are replaced by industrial extraction.

Together, their practices point to a radical idea: that textiles are not just objects, but can act as archives, healers, and blueprints for more just social structures.

Dhika’s understanding of materials began at home. Growing up in Jakarta, she lived in a multigenerational household where gardening and composting were daily rituals. “Every morning my grandma, my mother and my uncle would tend a small garden of vegetables, fruit, and roses in front of our house. It wasn’t big, but it was deeply loved,” she says. “My mother began composting, and over time built a small community around it – until almost everyone in the neighbourhood was doing the same.”

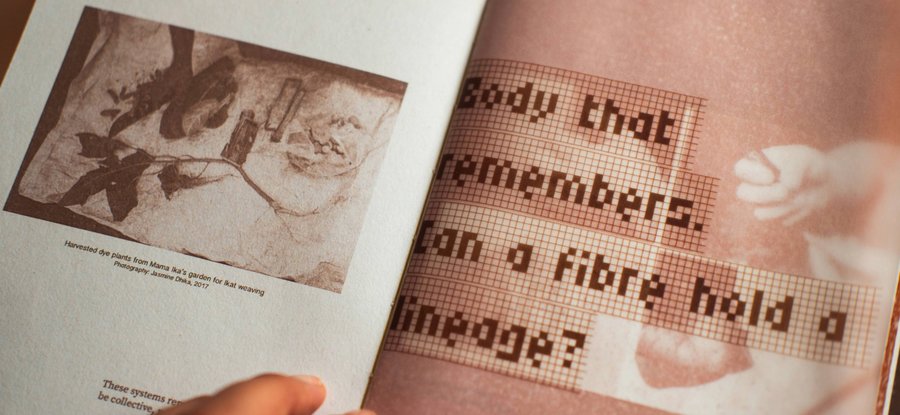

Later, learning Ikat weaving in East Sumba, she encountered the same principle at a larger scale: textiles as collective labour. “A single textile was never made by one person. It came from many hands – people who grew plants, spun thread, dyed with plants from their backyard,” she explains. “Food and textiles were never separate from the community and the land they lived in.”

When Dhika learnt about Ikat weaving in East Sumba, she encountered the same principle at a larger scale: textiles as collective labour

"[In East Sumba], food and textiles were never separate from the community and the land they lived in.” - Dhika

Holder’s understanding of textiles as communal knowledge echoes this, though it has taken shape within the diasporic spaces of South London. “Textiles have always brought people together,” she says. “Historically, in the Caribbean and in Black British communities in London, people would gather simply to make – to sit together and work with cloth,” she says. “I’ve been in spaces like that too, both ones I’ve created and ones I’ve entered, where people who’ve never met before begin talking because textiles give them an entry point.”

For Holder, cloth is not only a material, but a social language – one that teaches patience, listening and reciprocity, and creates conditions for people to share knowledge across generations. Her grandmother, whose photograph wearing a Madras dress sparked years of research, passed away before she could be interviewed. “There’s sadness in that, but also beauty. Memory becomes something you cultivate,” she says. “My grandmother had to rebuild home when she came from Jamaica to the UK – carrying fragments with her.”

For Dhika, healing begins with confronting how violently modern fashion has separated materials from meaning. Before studying at the RCA, she worked in the fashion industry and felt increasingly unsettled by how fibres arrived stripped of origin. “Fabrics arrived as commodities without stories of how they were grown, processed, or who made them. As someone working inside the system, and also as a consumer, that distance felt unsettling,” she says. “Even when brands talk about sustainability, it is often reduced to certifications or surface-level transparency, rather than a deeper relationship with material, labour, and place.”

From Holder's project 'Stepping Tru Healing'

Her practice now attempts to reverse that abstraction, by widening the framework of what counts as “knowledge”. She cites small scale farmers and weavers who can hold deep scientific and ecological understanding, but are often overlooked by traditional design education and the wider industry. “I feel like transparency and traceability should be a way to restore relationships so the textile or garment itself becomes harder to treat as disposable,” she says.

Holder’s engagement with textiles as a method of healing is deeply personal. Her RCA graduate project, Farìn – Caribbean patois for “foreign” – examined what it means to exist between places, cultures, and bodies. “It looked at healing generationally, ancestrally, and in the present. It was shaped by my mother’s illness, and by my own experiences with chronic health conditions,” she says. Copper, herbs, spices and silk became both symbolic and functional materials. “Copper is anti-inflammatory. It’s involved in dopamine production,” Holder adds. “I wanted healing to be both embodied and inherited.”

Rooting this ancestral knowledge in the materials chosen is a key part of both artists’ practice. Dhika’s project, Banana as Matter, Tradition as Knowledge, explores banana fibre as both a regenerative material and as a cultural archive. In parts of Indonesia, banana plants once structured everyday life: they were used as cloth, food, in ritual and as shelter. When coffee replaced them as cash crops, both plant and knowledge vanished. “The fibre still holds the rhythm of the land, the water it grew from, and the hands that once worked with it,” says Dhika. “It reminds me that materials are not neutral, they remember where they come from.”

Dhika’s project, Banana as Matter, Tradition as Knowledge, explores banana fibre as both a regenerative material and as a cultural archive.

“I would invite the field to slow down and listen to materials again. Sustainable futures don’t always come from new inventions, but from re-learning how to work with what already exists.”

Textiles MA Alumni + multidisciplinary textile designer

Holder’s material memory is carried through Madras – the checked cotton fabric that travelled from India to the Caribbean via colonial trade routes. Researching it revealed how fragile textile histories can be. “Unless you’re physically there, so much knowledge lives in oral histories. Libraries barely hold it.” Her project reframes Madras not as pattern, but as migration embodied. “Heritage might hold the possibility of repair,” she adds.

Where formal archives fail, both artists turn to material itself. Holder sees her work as a form of record-making. “Oral history is vital. But textiles are storytellers too. Cloth carries history in its fibres,” she says. Dhika echoes this, describing how her woven banana fibre retains irregularities – thickness, colour, texture – like terrain. “It felt like a landscape you could touch,” she says. For her, materials become disposable when their relationships are erased and restoring those relationships changes how we value them.

Both artists describe their time at the RCA as pivotal in deepening their understanding of the transformational power of textiles. For Dhika, a collaborative project on Japanese Wireweed – an “invasive” species forming new ecosystems – reframed how she understood belonging and extraction. “The environment became an active collaborator rather than a backdrop. This way of working directly shaped my banana fibre project,” she says. “It reinforced my belief in material-led storytelling, co-existence over extraction, and treating materials as living archives that carry memory, movement, and ecological relationships.” For Holder, who was a Virgil Abloh scholar, a guest lecture on ancestral wisdom – involving Kalinda practice and embodied memory – was transformative. “It helped me articulate what I already felt: ancestry isn’t abstract. It’s carried in the body,” she says.

If textiles are archives, healers and social glue, could they also help shape fairer futures? Dhika believes so. “I would invite the field to slow down and listen to materials again,” she says. “Sustainable futures don’t always come from new inventions, but from re-learning how to work with what already exists. When textiles are treated not as anonymous commodities but as living archives of place, culture and ecology, they can help us imagine ways of making that are regenerative rather than extractive.”

For Holder, this philosophy extends beyond her own work. Textiles become a way of thinking about how societies might hold pain without being defined by it — how care, joy and dignity can exist alongside history rather than in denial of it. Healing, she believes, is not about erasing what has come before, but learning how to carry it differently. “It’s about acknowledging what we hold – even when we don’t realise how heavy it is – and remembering that we are more than our trauma,” she says. “We deserve joy. We deserve to celebrate ourselves. We deserve to transform pain into something beautiful. We don’t erase the past, but we work with it to move forward.”