Key details

Date

- 19 November 2025

Read time

- 7 minutes

The Curating Contemporary Art graduate recently co-curated 'From Allegory to Algorithm' for RCA Photography’s participation at Jimei × Arles, featuring around 20 Chinese RCA alumni artists

You studied Social Anthropology at SOAS before completing the MA in Curating Contemporary Art at the RCA — what drew you from anthropology into curatorial practice, and how have those anthropological interests shaped your work today?

I moved from Social Anthropology to curatorial practice because I wanted to participate in knowledge production rather than just analyse it. At SOAS, I spent three wonderful years studying the anthropological lens and I thought it would be great to practice my thinking somewhere.

When I started my MA at RCA, I realised how careful I needed to be to apply anthropological concepts to art contexts. Curating offers a way to actively shape what gets shown, how narratives are framed, and which ideas gain visibility - questions that are urgent in both anthropology and the curatorial [space]. I am glad that anthropology provided me a critical lens to begin with but there are many challenges. I practiced as a so-called independent curator in mainland China for four years and I found it interesting that people embrace anthropology so much that it has become a buzzword. A lot of research, marketed as anthropological, was just a hook for fun conversations, or decorations for works that need an intellectual touch. So I became reluctant to apply anthropology to my projects. But it still shapes me because it sets an ethical guideline for me and warns me about my positionality and practice.

Could you share a key moment at the RCA that helped shape your curatorial voice or approach?

My curatorial voice is grounded in my ethical and political commitment which comes from anthropology, but my curatorial thinking and approach are shaped by training at the RCA. They both taught me how to look through the facade, to problematise the elite and technocratic core, and find the genuine and liberating voices.

Even since I started working, I have not had many chances to work with other curators. In most work environments, I need to worry about work ethics, division of labour, hierarchies… I do miss my time at the RCA, especially with my Grand Challenge group. A lot of my critical thinking around curator’s toolbox or the curatorial methodology comes from working with these amazing peers who are now active in various fields, as writers, curators, researchers, artists, etc. Every time I came across our collective’s Google Drive folder, I was amazed by the amount of thoughts that went into it. I still rely on the same method of working we developed together.

Harriet Zhang in a discussion on RMC's Anarchive

You’ve expressed an interest in cross-disciplinary collaboration. What does that mean for you in practice?

Cross-disciplinary collaboration is always in flux; at least my thoughts on it have changed over the last five years. It really depends on what disciplines are involved in a collaborative project.

I remember a few years back I liked criticising cross-disciplinary collaborations, because a lot of them are just appropriating each other and creating a romantic marriage between disciplines. Also, I always think cross-disciplinary collaborations need years and decades of research and practice together. To be honest, I am still contemplating its value. I agree with those who think cross-disciplinary collaboration is the future. As I am back to anthropology and researching medical knowledge in art and culture, I am seeing a lot of good potentials as well as harms.

Have there been moments when you felt you were pushing against conventional curating?

I don’t think I am pushing against conventional curating. There are a lot of wonderful projects, curated with a rather conventional and “boring” approach, which remain thoughtful in specific contexts. For example, at a traditional museum in Tibet, I was intrigued by how a team of curators and writers could weave different knowledge systems and thoughts together. They practice in a very conventional way. Another example is the strong bond between market and art in China. Certainly, there are things to be problematised but I think the rather conventional way of curating is quite effective. I like how distinctive each curator is and I really enjoy seeing their works.

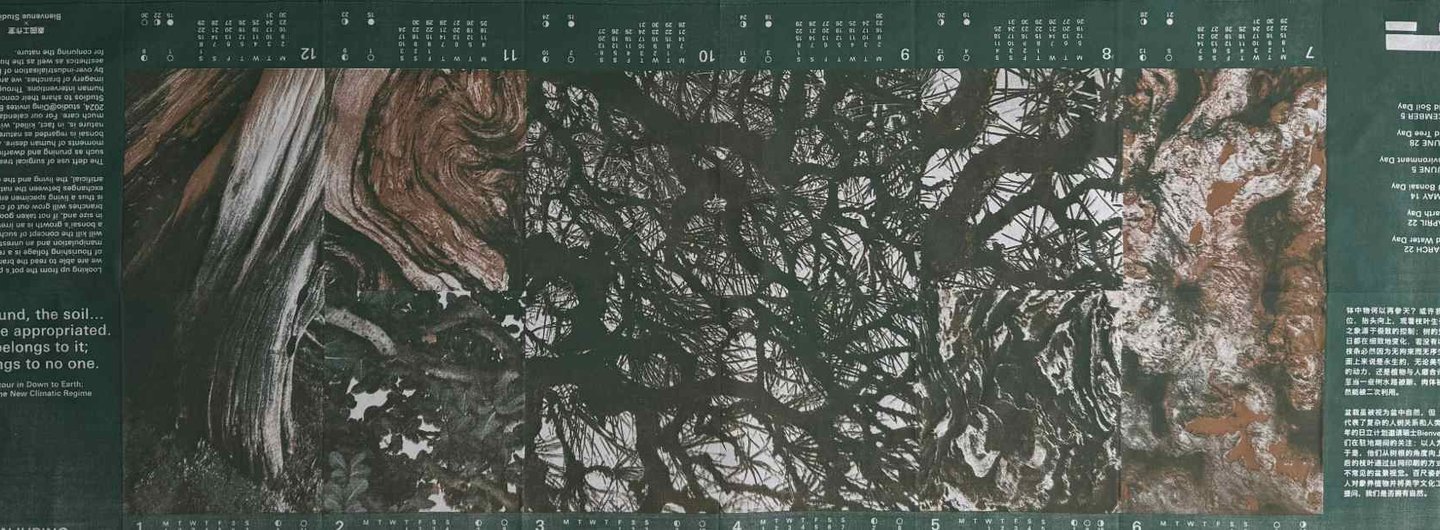

Detail from the poster for this year's Jimei x Arles International Photo Festival, Xiamen, China. An annual collaboration with Arles Photography Festival, France.

You were invited by Professor Rut Blees Luxemburg to co-curate From Allegory to Algorithm for RCA Photography’s participation at Jimei × Arles, featuring around 20 Chinese alumni artists. What was the thinking behind the title, and how did you approach selecting the artists and works?

This title is from RCA Photography but I can tell you about the Chinese title. I am bilingual and I see languages equally. I don’t like direct translating because, firstly, perfect translation does not exist, and, secondly, one of the languages is always compensating.

Whether it is the allegorical weight photography carries or the new technologies it embraces, photography does not pick a side. Nor does the exhibition want its audience to think we are moving away from allegory to embrace algorithms. In fact, a lot of photography programs in China are actually restructured to use new technologies. Traditional photography is in crisis on a phenomenological aspect. Why did I say the title could be misleading? In fact, RCA Photography keeps a distance from algorithms.

The Chinese title 新术维新 has its own way of representing this show. The first two characters “新术” means new means/techniques/apparatuses/art, referring to photography as a new technology still. The last two characters “维新”, ironically, means reform/restoration/renewal, mocking the cult of “newness” and the trend of constant pursuit of innovation. It questions the man-made narrative that treats each technological shift as a revolution. It is also a word play that performs a commentary on the crisis of photography that people often frame.

What are the main themes or questions you hope visitors will take away from the exhibition?

What we, the curators, really hope our audience to reach is an understanding of photography in flux. From allegory to algorithm, from camera obscura to neural networks, photography remains a complex practice negotiating visibility, authorship, and representation.

Contemporary debates around photography often frame technological change as a threat to the authenticity of the image. However, at the RCA, photography is understood as a medium in flux, constantly evolving beyond fixed definitions and predetermined outcomes. In this light, the algorithmic turn doesn't rupture photography's essence but continues its historical trajectory as a medium of construction and interpretation.

It is also a call for practitioners to have faith in their own ways of practicing.

Bowei Yang. The aggregation of dreams, a conversation about identity, China. 2020. From the Jimei X Arles exhibition. Courtesy of the artist.

As an RCA alumna now working independently, what do you see as distinctive about the RCA experience, particularly for Chinese curators and artists?

All artists in this exhibition are from China. We did not include international artists on purpose. We thought it would be interesting to show Chinese alumni and students’ works so that the changes that RCA has brought about could be more obvious. Did the RCA change their practice? Yes and no. Their practices were definitely shaped by the RCA, by the studio experiences, by their peers, by lecturers, tutors and technicians. However, I personally think that the artists were already aware of their intentions and what they’ve always wanted to do before coming to the RCA.

As a curator and someone who is obsessed with the ethnographic method, I loved talking to artists about their works and their experiences. What I have found is that, for example, some artists were given a safer environment by the RCA and by this city to express what has always been inside of them. Some artists explored cultures that are overlooked through a more defined approach.

What I see as being distinctive about the RCA is its approach to art and its emphasis on collaboration. These directions are embedded within its curriculum, its teaching, its research, its outreach programs, and many other aspects that I myself have not had a chance to explore.

What advice would you give to current students or recent graduates who want to pursue a similar path?

I don’t have any advice for students and graduates. However, I would say that finding one’s own horizon while also negotiating with reality is very difficult. Don’t be trapped. Be expansive. Be true. Don’t do anything that makes you uncomfortable.

Yihan Pan. The Slide of the World. 2025. From the Jimei X Arles exhibition. Courtesy of the artist. (1)

How do you see the role of cultural exchange in this project, and in your wider curatorial practice?

I tend to problematise the phrase “cultural exchange.” Rather than offering the usual line about its importance, I’m increasingly pessimistic about the conditions in which such exchange is expected to happen. Many parts of the world are becoming more conservative, even violent, and it’s difficult to separate the idea of cultural exchange from these broader realities. In the case of mainland China, for example, the idea of “exchange” often requires immense translation and interpretation; structural barriers are well known locally but rarely openly discussed, and demonisation happens both inside and outside the nation-state. Many cultures face similar tensions. Genuine exchange becomes impossible when friction and division are the goal.

Cultural exchange matters deeply to me—but more as a person in the world than as a curator. Curators are often expected to smooth contradictions, perform neutrality, and be diplomatic and challenging at once. My practice is instead about creating space where structural barriers, uncomfortable gaps, and real disagreements can be named rather than resolved. It’s not always comfortable, nor does it align with institutional expectations of what “cultural exchange” should produce, but I think it’s more honest—and ultimately more meaningful—than performing an exchange that glosses over the conditions that make true dialogue so difficult.

Looking ahead, what’s next for you? And what is one question you’re currently asking yourself as a curator?

I am looking forward to my research on medical knowledge in the art industry and visual culture. There will be a few projects on themes like medicalisation, hunger, weapons and musical instruments. I will also be in a new research collective with some wonderful researchers and curators.

One question I am currently asking myself is how do I find my own collaborative method that brings anthropology and art together.

Zhuoheng Li. Back to river, from series Noctiflorous. 2024. From the Jimei X Arles exhibition. Courtesy of the artist.