Key details

Date

- 27 August 2025

Read time

- 9 minutes

Designer, educator and curator Zarna Hart (RCA/V&A MA History of Design, 2023) on heritage, archives and opening up space for new voices in design history

You're originally from Trinidad and Tobago. How has that heritage shaped your approach to design history and storytelling?

I think the lack of formal archiving in Trinidad is probably what first motivated me to do the course. Trinidad has such a rich and amazing history, but we have such a poor way of documenting it. The idea of archival practice was fascinating to me because it simply didn’t exist in the same way back home, whereas in the UK—with institutions like the V&A—there’s such a strong legacy of it. I saw the course as a great opportunity to explore what that might look like in the context of Trinidad. Storytelling there can often be very fleeting, without the intention of recording or passing it on, and that really shaped my interest.

But over time, I began to think that perhaps it wasn’t so much a lack of archiving as a completely different way of doing it. Societies like ours embrace the temporality of things, where history is carried through conversations and memory rather than preserved in institutions. Doing my master’s helped me to understand and value that perspective, and it was an amazing experience—I had nothing but a good time during my time [at the RCA].

That's great to hear, and that must have been a real seismic shift for you to be able to reflect on it as neither better nor worse, just different.

Absolutely. I think a lot of Trinidadians who came to the RCA traditionally pursued the applied arts—things like textiles, jewellery, and so on. But now I feel that academia is beginning to have a kind of reawakening in the Caribbean. The challenge, unfortunately, is that the resources to support it are still very limited. That’s why I feel incredibly fortunate to have had the opportunity to study here and experience this path in design history.

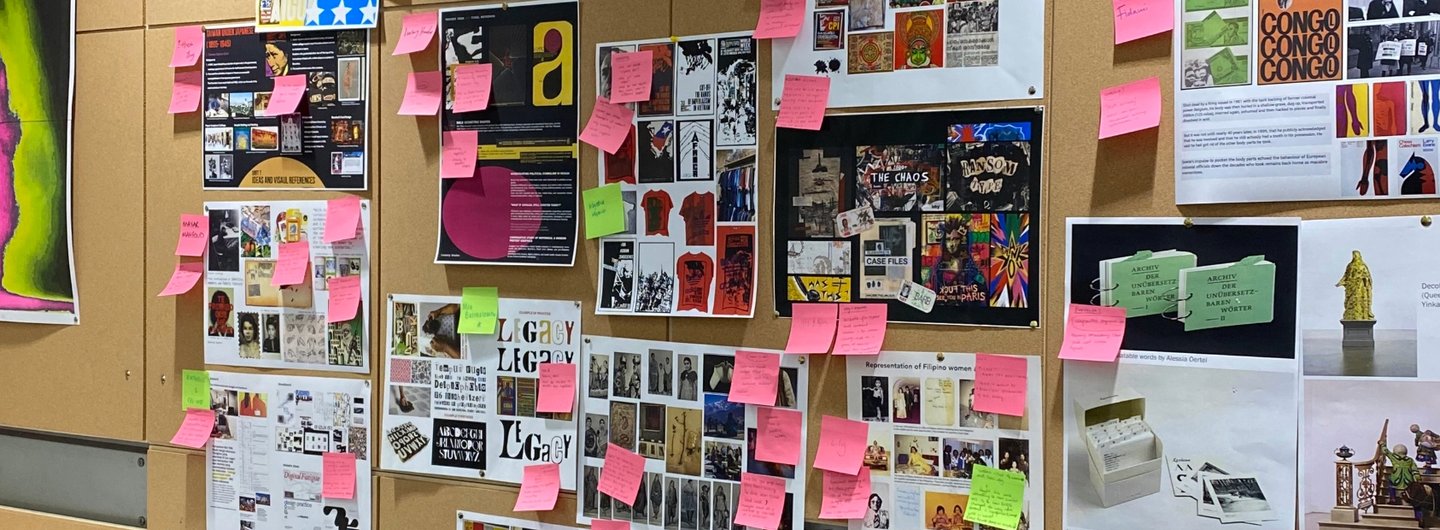

Typographic workshop led by Mia Bartholomew, one of Zarna's students at BA Graphic Design, UAL Camberwell College of Arts, February 2025

I know you’re living in London still, but do you have an interest in bringing back what you’ve learnt to Trinidad?

I think about this every day. Sometimes people categorise my work as a form of decolonising histories, but under the context of the Caribbean I’m not sure that really makes sense. That’s a constant tension for me, because in many ways the Caribbean is still very colonised, often without realising it, through traditional systems and ways of thinking that persist today. So I feel that kind of discourse about decolonisation is really more relevant here than back home.

What I do think about a lot is knowledge exchange—how certain skills and approaches can be shared, creating opportunities for people in the Caribbean to contribute to the conversation and develop their own views on what history can look, sound and feel like. As for my own practice, if I wanted to make something truly and uniquely Caribbean, I think I’d need to spend a significant amount of time back there, rooted in that landscape and with its people.

It's great to hear you had such a good experience on your course, were there any stand-out moments that made you shift your perspective?

I had been working as a graphic designer for about seven years before starting my master’s, and it was such a different environment from traditional academia. In design, things have to get done fast and before the deadline, and I reached a point where I felt the work I was doing wasn’t really contributing to anything—it was simply a means for a company to make more profit. I wanted to take time to pursue something more meaningful, and the transition into academia was massive for me. Suddenly I was in a room with people who were much more experienced in that world, and that was groundbreaking—I learned so much not only from the incredible staff but also from my peers, who were exceptionally smart. The friendships and community I built in that space have been incredibly fulfilling. Looking back, I’d say that’s been one of the major highlights for me, alongside the challenge of really putting myself into the fire, which has also been transformative.

Zarna Hart at Industry Leaders Talk at Run That Back, October 2024

So being in that environment and surrounded by those kinds of people, how did that propel you into your next chapter after you graduated?

From the beginning of my master’s, I knew I didn’t want to go back into graphic design—though I’m sure my graphic design friends will tease me for saying that. I realised I enjoyed learning about the field far more than practicing it, and doing such a research-driven programme really changed my outlook on design altogether. It gave me a completely different way of seeing design making.

I also noticed that my peers in academia seemed so much more fulfilled and passionate about their work than many of my colleagues in industry. Of course, academia comes with a big pay cut compared to graphic design, but it offers something else: self-development, discovery, and a real sense of camaraderie. The encouragement and community I found on the course helped confirm my decision to follow this path. Plus, the opportunities I had—whether curating exhibitions, collaborating with partner institutions, or understanding how different career systems operate—gave me a strong stepping stone for whatever comes next.

Your dissertation Not All Trunks Float explores Windrush print and oral culture. What sparked your interest in using orality as a method of design history?

It took me a while to land on where I wanted to focus, partly because at the time there was so much discourse around the Windrush generation, especially in relation to fashion and the economic aspects of trade and exchange. Those areas didn’t really interest me, and coming from a graphic design background, I was more fascinated by the ephemera surrounding that culture—what was being written about Windrush at the time, and what the scholars of that generation themselves were producing. I found it especially interesting to look at essays and writing from figures who later became prime ministers or politicians in Trinidad, and to see how they articulated and documented their experiences in London. That led me to think about archiving in unorthodox ways, comparing these written accounts with the oral histories I found in the British Library.

Ultimately, I became less focused on a single specialism and more interested in how different cultures, particularly those from the Caribbean and other global majority backgrounds, construct their own systems of knowledge, memory, and archiving. Reading about how this is also expressed through First Peoples and ancestral practices of archiving has been especially fascinating. So in a sense, my path was part rebellion against the expected route and part desire to create something new—bringing together conversations and perspectives that hadn’t yet been pieced together.

“To suddenly be immersed in a system filled with complex theories and concepts—ideas no one in my family had ever spoken about—was both exciting and intimidating.”

Curator-designer-educator + RCA/V&A MA History of Design, 2023

Zarna Hart working with the curatorial team at the V&A during research placement in 2023

Am I right in thinking you didn’t conduct interviews yourself, but instead worked entirely with existing historical records in order to interrogate the record-making process itself?

Yes. The only people I interviewed were those responsible for managing the archives and acquisitions. I wanted to understand the detail behind what was being accessed, what wasn’t, who was responsible for acquiring certain materials, and why some things were added or excluded. That really helped me to contextualise different perspectives around archival systems we don’t usually think about. One of the privileges of being in London is that there are so many incredible resources within such close reach, where you can access almost anything. But as learners, readers, or members of the public, most of us don’t know who controls that access or how much power they hold in shaping what we are able to consume. For me, interrogating that process was more important than re-interviewing members of the Windrush generation, because it was about questioning the structures of record-making itself.

Do You Buy This? Exhibition, curated by (from left) Cas Bradbeer, Sufiyeh Hadian, Amber Kim, and Zarna Hart, at the Ugly Duck, August 2023

How have you carried what you learned from your dissertation into your current practice and the work you’re doing now?

In the past few years I’ve also been invited to collaborate and curate exhibitions with artists, which has been a really exciting extension of my practice. As a curator, I’m particularly interested in how audiences become participants in a space—how they receive and process the information being displayed. That connects closely to the questions I explored in my dissertation, and it’s been rewarding to see how teaching, curating, and research can all feed into one another.

Most recently, through UAL Camberwell College of Arts, I received funding to design and run a programme for final-year graphic design students from global majority communities in and around London. The idea came from data I’d seen as a lecturer, which highlighted persistent attainment gaps between these students and their white peers. Rather than framing it as “extra help,” the programme created dedicated time and space for students to strengthen their practice, build confidence, and feel recognised as designers already. The pilot has been incredibly exciting, and I see it as an important step in reimagining what support in design education can look like. And UAL Camberwell College of Arts has offered to provide funding for it again, which is really exciting.

Of course, my programme is just working with a small group of students within a much larger design student population in London—and across the UK—and it breaks my heart to think that the same challenges could be happening nationwide. I often reflect on my own experience as a design student in the UK back in 2014, coming from a country with no design museums and very little design discourse. To suddenly be immersed in a system filled with complex theories and concepts—ideas no one in my family had ever spoken about—was both exciting and intimidating.

MRKT stall & display, co-founded by Zarna Hart and Ravista Mehra, at SOLD OUT Fair, June 2025

“My advice would be to be brave, put yourself out there, and stay open to opportunities—whether that’s new friendships, collaborations, or experiences beyond the curriculum. For me, it was those opportunities that made the course truly special.”

Curator-designer-educator + RCA/V&A MA History of Design, 2023

Earlier in your career you had a placement at the V&A. What was that experience like, working within such an iconic institution, and were you able to bring your own ideas and perspectives into a space so established?

I worked with the Design and Digital department at the V&A while I was a master’s student, and it was such an incredible experience. I’ve always been fascinated by how museums function and the people behind them, but being inside that environment was something else entirely. You’re surrounded by some of the smartest, most passionate people in the world, people who have spent years studying the tiniest details of something much larger, and it was inspiring to witness their dedication. I was also lucky to have a manager who encouraged me to shape the placement around my own interests, connecting me with people who could help me explore ideas linked to my dissertation, while also exposing me to the wide-ranging acquisitions and objects that the museum was working on.

The experience gave me huge respect for people working in museums and cultural institutions—the hours are long, yet they approach their work with so much energy and passion. At the same time, it also made me reflect on whether this was the right career path for me. The reality is that positions in museums are very limited because once people are in, they rarely leave—and understandably so. But it does mean that knowledge and influence often sit with a select few, which can create a kind of stagnation. That isn’t a criticism of the V&A specifically, but more of the wider academic and cultural system. For me, it reinforced the importance of finding ways for more voices to contribute, and for knowledge exchange to feel more open and dynamic.

Finally, what advice would you give to current or prospective Design History students at the RCA?

I would say wherever you are in the journey, take every opportunity you can. My programme was only a year long, and that can feel overwhelming—especially if you’re coming in without much prior knowledge, as I did. But it also gives you the chance to completely immerse yourself, and you’d be surprised at just how much you can absorb. I remember worrying that, as a slightly older student who had already been through a career, I wouldn’t be able to keep up with my classmates. But the RCA has such a fantastic network, and I was able to access so many resources, both within the university and through its connections with places like the V&A. My advice would be to be brave, put yourself out there, and stay open to opportunities—whether that’s new friendships, collaborations, or experiences beyond the curriculum. For me, it was those opportunities that made the course truly special.

Keep In Touch Exhibition, curated by Zarna Hart and Ravista Mehra at Host of Leyton, November 2023